After I was as convinced as much as it was possible to be convinced that Donna had definitively dumped me forever, I drowned my sorrows by writing the senior play. I’ve always drowned my sorrows by writing stuff. If I had no sorrows, I wouldn’t ever write diddly.

Writing the senior play was my big claim to fame. The high school in Michigan didn’t have the money to buy the rights to a real play, so I said I’d write one. I stuck in a scene about a guy who had recently had his heart utterly crushed and broken forever. Then I played the part of the brokenhearted guy and gave myself lots of good advice. Ha! I was the student director, too. I did it all. The play was a big success. I had to take a bunch of bows. People kept clapping. And all of a sudden, all kinds of new chicks started coming up to me in the hallways, batting their eyelashes, bumping their breasts into my bare arms — cheerleaders, actresses, smart chicks with glasses.

Then, right in the middle of all that, Mrs. Miller flunked my ass, and I didn’t graduate. What chick’s going to want to mess with some guy who flunked out of high school? No chick, that’s what chick. No wonder I had a chip on my shoulder. I’ve still got a chip on my shoulder. I’ll always have a chip on my shoulder. Talk about completely fucking up a person’s life forever. Oh, well. My life probably would have gotten fucked up forever somehow or other anyway.

The day after I didn’t graduate, we all, me and my two younger sisters and my mother, flew out to California to be with my father. He’d been transferred there in April, and the insurance company he was working for gave everyone a free plane ticket. How could I pass it up?

The picture I had in mind of California was row upon row of sun-bleached blond girls in bikini bathing suits lying around on sandy white beaches waiting for random guys to come rub Coppertone on them — and my father had written a letter telling us that the house he’d rented was three blocks from the ocean! Where there was an ocean there had to be a beach, right? Hot sand? Damp towels? Salty sweat and a melting cherry Sno Cone dripping down some cute little California surfer chick’s suntanned throat?

Wrong.

What my father’s letter didn’t say was that the house he’d rented was in a place called Pacifica, which, next to maybe Baffin Island and Tierra del Fuego, is easily the third most inhospitable place on the planet. According to the people who live there, Pacifica stays “socked in” all summer, and what “socked-in” means is that it’s so fucking freezing-ass cold and foggy and windy that you can’t see across the street let alone down to the ocean, and even if you could see down to the ocean, which you can’t, you still couldn’t see any beach because, number one, there isn’t any beach and, number two, what passes for a beach is nothing but jagged rocks with huge cliffs towering above them, so that even if you could see what passes for a beach, there wouldn’t be any girls on it unless some poor blind paraplegic chick accidentally rolled her wheelchair over the edge of one of the cliffs, and even then she wouldn’t have on a bikini bathing suit unless she was also so hopelessly crazy you wouldn’t want to have anything to do with her anyway.

I didn’t blame my father. None of us did. Well, not for that. We took his word for it that the weather had been nice the day he’d rented the place, and besides, there were plenty of other things to blame him for — like those three blocks from the ocean he’d bragged about. What the letter didn’t say was that each block was half a mile long and went straight up the side of a mountain, so that if you were ever stupid enough to risk life and limb by venturing out into the blinding wind and fog long enough to try to make it down to the tawdry little shopping area at the bottom of the street, you’d have to be Edmund Hillary to get back home again.

My father was having a hard life himself. His job wasn’t what it was cracked up to be. What had sounded like a lot of money in Michigan wasn’t much in California. I don’t know which of us was the most disappointed. I think it was around a five-way tie. We all had different ideas of what things were going to be like in California, and none of them was anything like what we found in Pacifica.

My sister Nicki, who had just turned fifteen, did nothing but sit on the bare floor in her room, wearing every stitch of clothing she owned and listening to Buddy Holly sing “Everyday” over and over so often she wore out the grooves on the record. My father tried to cheer her up as best he could, first by trying to play “Petty Sue” on the mouth organ, then by getting her her own phone — both of which turned out to be as disastrous as everything else he’d done so far that year. If anyone could have played “Peggy Sue” on the mouth organ it would have been my dad, but the fact is it can’t be done, and as for getting Nicki her own phone, yeah, she always had wanted a phone of her own, but the son of a bitch never rang, and she didn’t know anyone she could call except back in Michigan, which nobody could afford to pay for, and it only would have made her more homesick than she already was even if anyone could have paid for it.

My poor mother. All she ever did was try not to cry in front of my five-year-old sister, Tuney…and poor Tuney! She thought for all the world that we were going to be living next door to Disneyland. Ha! The only thing remotely resembling Disneyland that we could reasonably get to on the best of days was a drafty, overpriced, mildewy movie theater down in the tawdry shopping area at the foot of that bloody mountain. I didn’t help much.

Tuney had heard that “The Snow Queen” was playing at the aforementioned movie theater and I told her that I’d take her to see it but that I didn’t have any money to buy myself a ticket. She got all excited and jumped up and down and begged and pleaded and cajoled and, in short, convinced me that she wanted to see “The Snow Queen” so excruciatingly badly that she gladly agreed to pay my way with the silver dollar she got from her grandmother for Christmas.

The story has become something of a family legend. The way Tuney tells it is that I tricked her into giving me her silver dollar then took her to see “The Apartment.” And, on the face of it, that’s true. I did. Well, not the “tricked her” part. I didn’t trick her. “The Snow Queen” had been replaced by “The Apartment” that same day, and I truly did not think that she would really want to turn around and walk all the way back up the side of that god damn mountain again without seeing some movie, any movie, so I took her to see “The Apartment” instead.

The day after our disastrous trip to see “The Snow Queen,” I got the hell out of the house in Pacifica and hitchhiked down along the coast highway until I came to the California I’d had in mind back in Michigan. It started just past Malibu. I didn’t have any money. I ate food out of garbage cans, slept on beaches and feasted my eyes on sun-bleached blond girls in bikini bathing suits from dawn to dusk — until having no money and a third-degree sunburn had me heading back up toward Pacifica again.

That was when I got the job on that yacht I was talking about. This colored guy picked me up. He was driving a white Cadillac and had a white girlfriend. His name was Lucius. His girlfriend was a nurse, “A noyse,” he called her, being as how he was originally from Brooklyn. Lucius told me to show up at the Lido Shipyard in Newport Beach the next morning and he’d have a job for me. I slept behind a billboard, hitchhiked back down to Newport Beach and started work that same day.

I was a good worker. I did everything no one else would do, like paint the inside of the chain locker. I had Rustoleum in my eyebrows for weeks.

Toward the end of the summer, when we were just about through renovating the whole huge boat from stem to stern, the captain told me I could stay on as part of the crew when they took it on a trip around the world. I had it all pictured. Hawaii. Fiji. Bali. Bangkok! Then I don’t know what the hell happened.

Well, I got fired, is what happened — for going for a ride on the Ferris Wheel on Balboa Island with the owner’s son’s girlfriend.

Her name was Paris. She had long blond hair, freckly thighs and zinc oxide across the bridge of her nose. I didn’t know she was anyone’s girlfriend. She didn’t say she was anyone’s girlfriend — and she sure didn’t act like she was anyone’s girlfriend. But she was. And the owner’s son told the owner to tell the captain to tell the foreman that I was fired and that was that — no trip around the world, no job, no money, no place to live, no nothing. I hitchhiked back up to my parents’ house.

It was September. My family had moved from Pacifica to San Mateo and were living in a modest little three-bedroom house in a place called San Mateo Village — which was how I ended up at Hillsdale High School doing this scene in a drama class with some Mormon kid from Salt Lake City.

I was the cop. Elliot was the crook. I had to give him the third degree. That was the scene. I forget what play it was from. The script had been run off on a mimeograph machine. The ink was purple; the ink smelled purple.

He had on a black and maroon striped shirt and was sitting in a metal folding chair pulled up next to a green cardboard card table. There was an open pack of Camels in his shirt pocket. I stood over him with my sleeves rolled up and the stub of a pencil behind my ear. A hundred-and-fifty-watt light bulb glared into his face. Sweat beaded up on his scalp. His hair was dark brown, almost black, and straight, and stringy. He had the beginnings of a widow’s peak, but his hair was so long in back it curled up at the ends like fishhooks. A muscle twitched in his cheek. Blood wiggled through an artery in his temple. The corners of his mouth jerked into inappropriate smiles. His lips trembled. I could see each individual follicle of the sparse whiskers on his chin and the pores on the sides of his nose and the veins in his nostrils and the hair in his ears. A drop of sweat trickled down his temple. His hands were shaking. His ears were shaking. His eyelids were puffy. And his eyes. I still can’t say what his eyes looked like. Well, they were brown, but I can’t describe the expression in them. It was pure fear — abject panic. He was scared to death. His eyes darted back and forth, into and out of every murky corner of the fidgeting auditorium, getting more and more terrified.

Then he looked up and directly at me for the first time. That was the last straw. There were tears in his eyes. He looked like he was about to wet his pants. I wanted to stop everything right there and tell him, hey, man, come on, it’s a drama class. Yeah, sure, I knew he was supposed to be acting like he was scared, but he wasn’t acting, he was really scared, he was terrified — and even if he was acting, there comes a point when it doesn’t matter; like if you wet your pants in front of whole god damn drama class, how could it possibly matter whether you were just acting or not?

I burst out laughing.

I couldn’t help it.

I couldn’t read the lines. I tried, but when he looked up at me, I had to laugh. Ralston had to make us start all over. That happened three times — him looking up at me, me laughing, Ralston making us start over.

The fourth time, Elliot lurched out of his chair, kicked it across the stage, tossed the script out into the audience and stormed over to the emergency exit door, leaving sheets of mimeograph paper rocking slowly back and forth down through the sudden utter silence of the cavernous auditorium. I felt sort of bad that I was screwing up the scene for him, sure, but on the other hand, what the hell did he think, it was Carnegie Hall? It wasn’t. It was a two-bit drama class in a high school I never should have been at in the first place. My girlfriend was in New York, dancing on Broadway, getting rich and famous. And, as for me, I should have been in Bali by then. I should have been halfway to Bangkok.

Over in the wings, Elliot took a few deep breaths, whipped out a comb, slicked back his hair, and came out onto the stage again. One of the kids in the front row offered him a new script. Elliot waved it off. He brought his chair back, sat down again, and we tried doing the scene one last time. The light bulb glared. Sweat beaded up. His cheek twitched. His mouth trembled. He looked at me. There were tears in his eyes. He was about to wet his pants. I laughed. Ralston didn’t say anything. The curtain closed. We were alone back there.

“Sorry,” I said.

Elliot didn’t say anything. He hadn’t said anything the whole time. He wanted to say something. It was plain to see that he was trying to think of something suitable to say, but by the time I got around to telling him I was sorry, he couldn’t have said anything even if he’d thought of something to say, and finally he just hissed at me. He bared his teeth and hissed at me like a cat — but not even a cat, something more primitive than a cat — a lizard, or a snake, or a sea urchin.

A current of electricity shot through me. It felt for a second like I was going to hiss right back at him, but then it dawned on me that I didn’t have to put up with some California dipshit hissing at me like a fucking sea urchin no matter what I did, and I winked at him, instead — just a quick little wink with my right eye. That was the best thing I could have done. It caught him so completely off guard he had to smile. Then he caught himself trying not to smile and that made him almost have to laugh. It was like the sun coming out. All of a sudden, his eyes were so full of such affection for me it felt like he was about to jump out of his chair and come dance me around the stage like a rag doll — as if his whole life he’d been waiting for someone to wink at him, and no one ever had.

Elliot couldn’t just let it go at that, however, and acted like he felt sort of sorry for me.

“How about I play the cop?”

“You should just get someone else, man. I can’t act worth a shit. I don’t know why I even signed up for this stupid class in the first place.”

“There’s nothing to it. Just be a cop. Be thinking about what your wife’s going to be cooking for dinner while you ask me questions.”

“I can’t. I’d be picturing her cooking snakes or something. They’d be jumping out of the pot. She’d have to keep hitting them on the head with a spoon.”

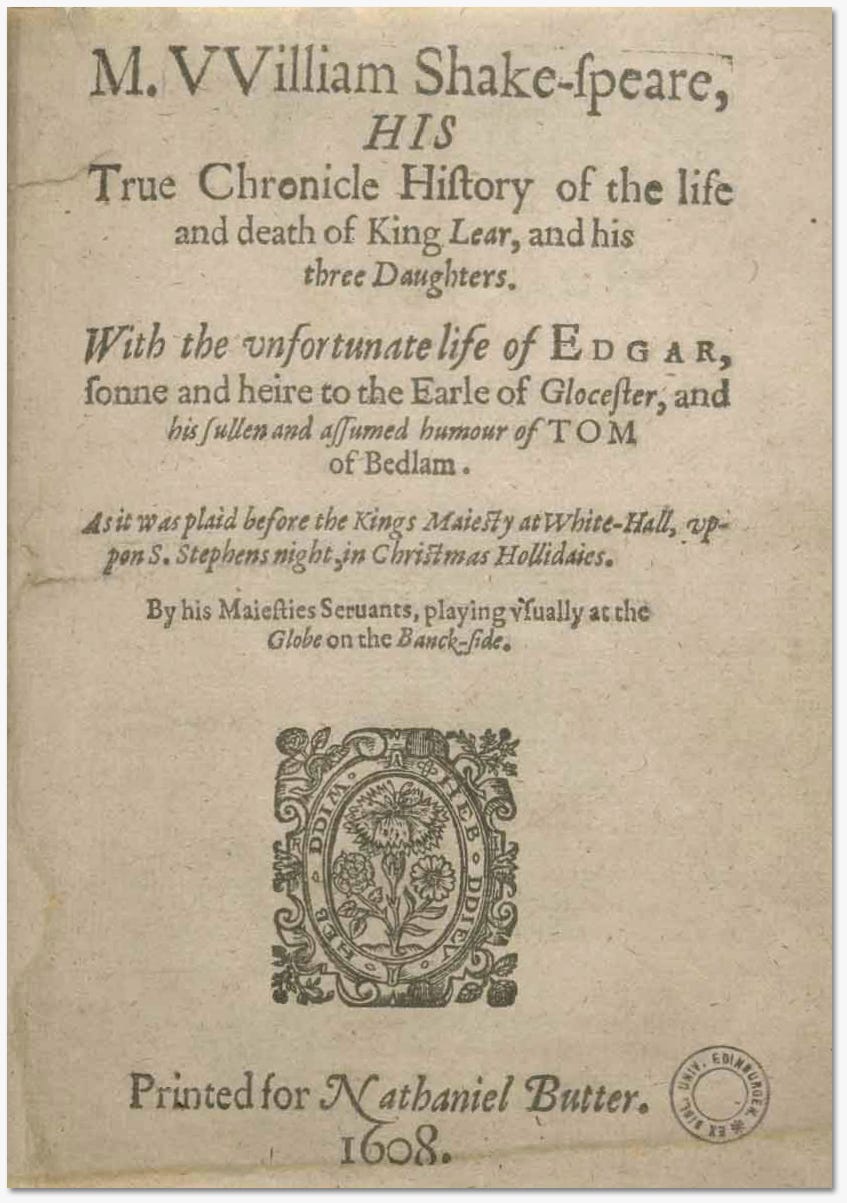

“Hey, that’s King Lear! That’s my favorite line. ‘Cry to it, nuncle, as the cockney did to the eels when she put ’em i’ the paste alive; she knapped ’em o’ the coxcombs with a stick, and cried, “Down, wantons, down!” ’Twas her brother that, in pure kindness to his horse, buttered his hay.’”

“Yeah, well, I don’t know anything about any of that. All I know is trying to do something I can’t do makes me laugh.”

“So, quit trying.” He shrugged.

I made him feel superior. He liked that. He made me laugh. I liked that. We got to be friends. That was all there was to it. We stayed friends forever — or for however long forever might have been back then.

I don’t know the meanings of words anymore.

Forever seems about right.